Cecil Beaton isn’t the easiest person to unwrap. Head to your nearest bookstore — there’s ample shelf space dedicated to dissecting his life. The Englishman was a consummate polymath: an accomplished photographer, painter, writer, interior designer, scrapbooker, costume and set designer, whose prolific career spanned both decades and continents. Some may know him best for his iconic images of Hollywood’s grande dames: Greta Garbo, Marlene Dietrich, Joan Crawford. For others, his name evokes the award-winning fashions in My Fair Lady and Gigi, both of which nabbed him an Oscar. Just when you think you know everything about him, you realize there’s yet more to uncover.

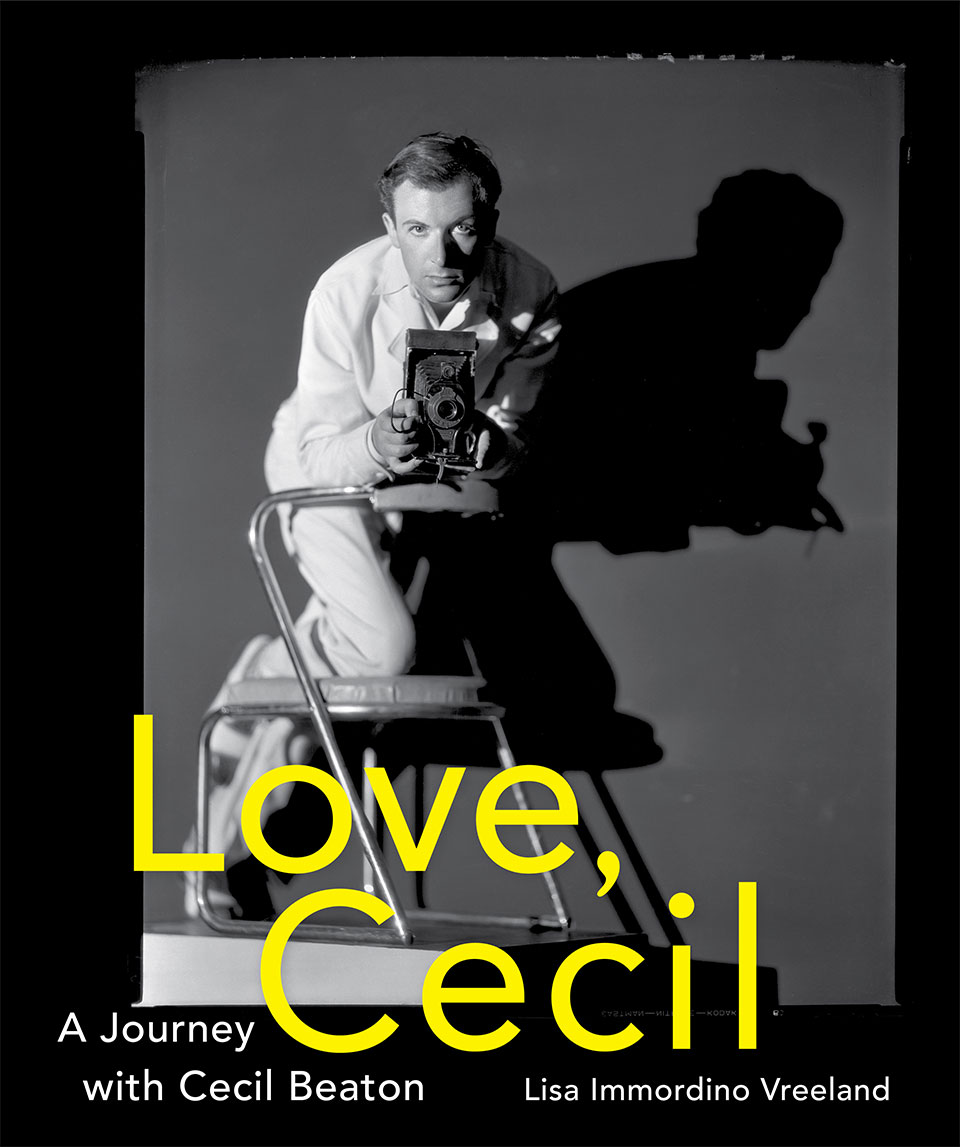

Enter author and filmmaker Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who takes a new look at the creative legend in a just-released book and upcoming documentary, both titled Love, Cecil. She covers the myriad chapters of his life, from his early years among the social swirl of London’s bohemian Bright Young Things to his little-known war and still life photography to his famously caustic burns. (Sample snark: “In spite of her success, her aura of freshness and natural directness, she is a rotten ingrained viper,” he wrote of Katharine Hepburn. “She is a dried-up boot.”) Here, we chat with Immordino Vreeland on all things Beaton.

Why Cecil Beaton…

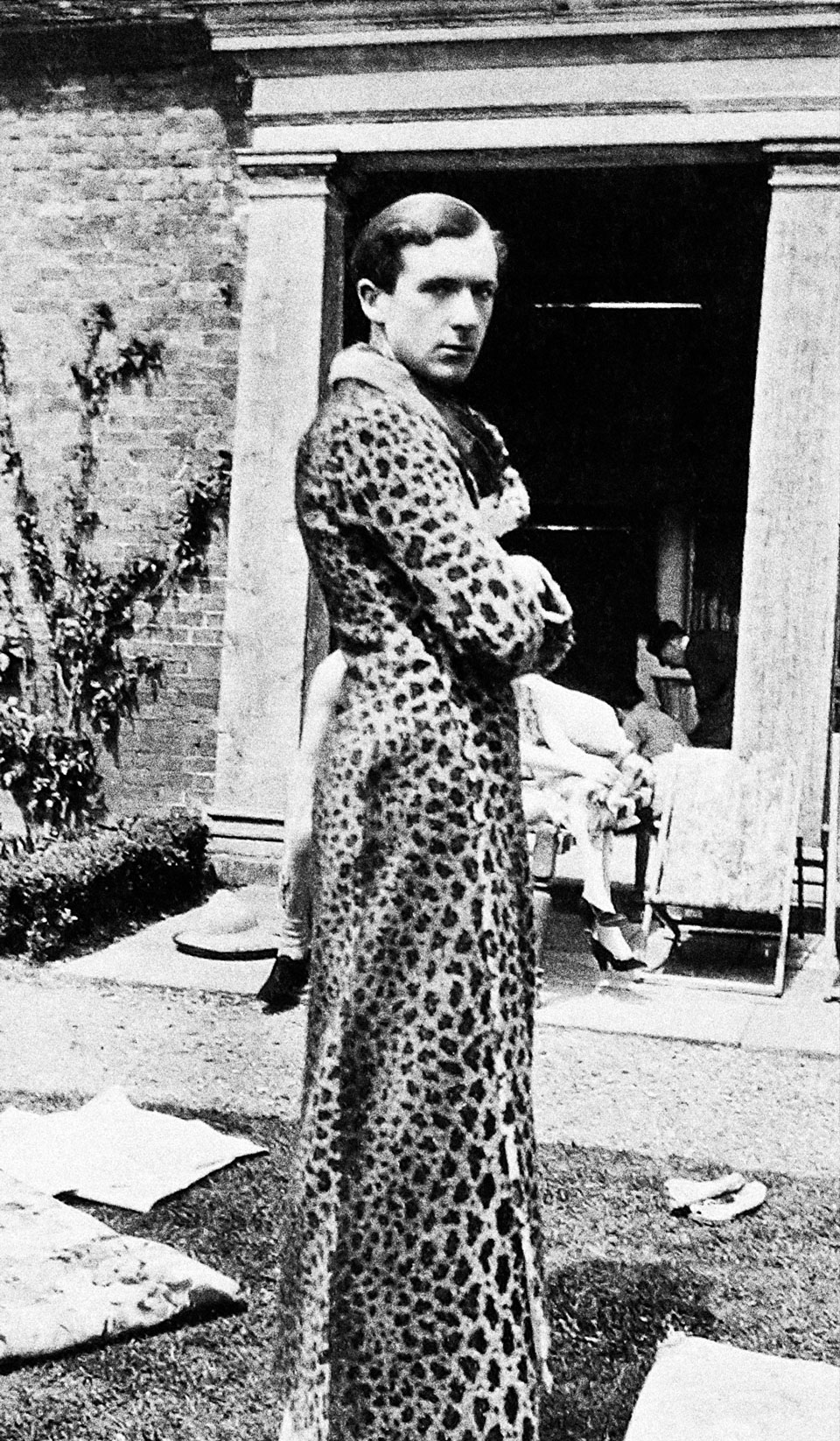

My interest in Cecil Beaton began when I made the documentary, Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel. I knew they were lifelong friends. He was in the film and was just so great. I’m clearly attracted to 20th Century creative icons — first, I did Vreeland, then Peggy Guggenheim and now Beaton. I like my characters to have this sense of reinvention — all three had it. Beaton was the most aggressive about it, in a sense, because he had this incessant ambition that was very calculated from a very young age. He wanted to be somebody else and change his life — it drove him completely.

On my book, Love, Cecil…

I wanted it to look modern. There are so many Cecil Beaton books, but they all look the same and there’s a lot of repetitive imagery. With this book, and film, there’s a good balance of recognizable images — like Greta Garbo — as well as imagery people haven’t seen. I love the still life of the potatoes and the picture of the sheep in the chapter on photography — nobody would ever use that. It’s very striped down and not a recognizable Beaton image, which I like.

The most challenging part of this project…

The obscene amount of material.

My research involved…

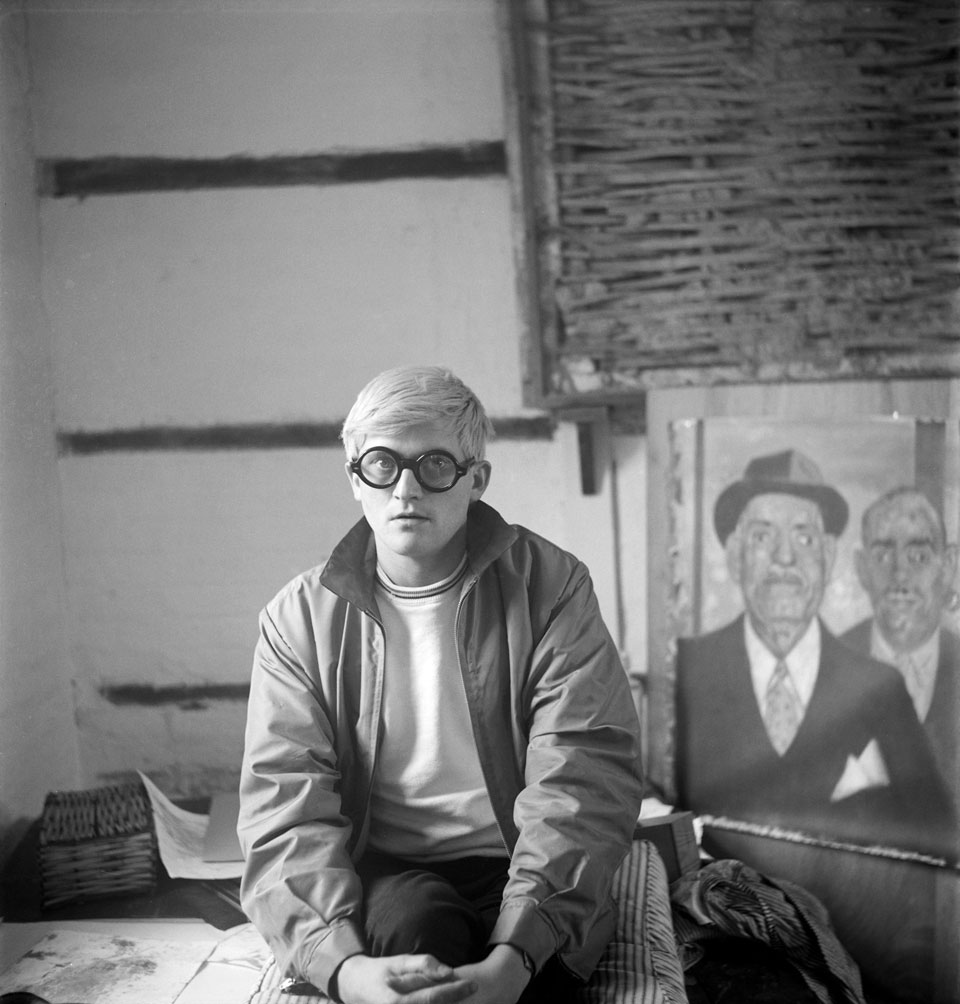

There was so much to choose from and that was exciting. All of his archives are based in the UK: Sotheby’s, which has his largest photographic archive, the Victoria and Albert Museum, St. John’s in Cambridge…. St. John’s has all of the letters he wrote to friends and all of his personal diaries. I could see an intimate view into his relationships — and to the 20th Century. In his references to a painting or a book or a play, he was really recording the 20th Century from the front row. And he wasn’t just a bystander; he was in the middle of the creative and cultural elite of that era. And, you know, this wasn’t just for a decade — this was from the Twenties to the Seventies! He was just as comfortable hanging out with Edith Sitwell, Jean Cocteau, and all of England’s royalty as he was with Divine, Andy Warhol and Mick Jagger.

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

On Beaton’s creativity…

He sacrificed everything to be creative. Even today his creativity stands out because he not only took incredible photographs, but he was a beautiful writer and sketched and painted people. He did stage and film design, too.

On his writing (and handwriting)…

He’s published 38 books — that’s nothing to laugh at. He’s a very, very good writer. But his handwriting — he has the kind of handwriting where you never lift the pen off the page. It’s constant. Ok, he does put periods, but the handwriting is illegible. I think there are probably more revealing things I would have learned if I could read more of the actual diaries. It would be fantastic if one day somebody creates a body of work just from those diaries.

Beaton on photography…

He never claimed to be a photographer’s photographer. He never claimed to understand the technique, except he was highly knowledgeable. He wrote a book, The Magic Image, that is all about photography. His insight was incredible. He spoke about photography in such an intelligent manner. He always pretended to be not so wise about all of this, but he really was.

© The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sotheby’s

My favorite Beaton body of work…

I have a soft spot for photography myself, so it would be his photographs. I do love his portraiture, but there’s something about the clean line and energy of his war photographs that I really love. He captured the feeling of those soldiers at that time and I don’t think anyone has really captured WWII like that.

On the unifying factor behind his work, given the range…

Being an aesthete and looking at the world in a certain way. From his fashion photography to his portraiture, there’s this finished veneer; there’s a beauty to them. Take his WWII photographs — they’re slightly sexualized, which is not the typical eye of a war photographer. For him, everything was a theater. When you’re manipulating your whole life at such a young age, when you’re able to create this world around you that you did not have and want to be a part of, your whole life is a stage.

On his personality…

He was a flawed character. He never quite felt good enough. He was a tough personality, and was considered a snob. His big thing was that he always felt insecure. And I think that showed in the way he treated people sometimes. What drove him was his work, that’s where he found his home. He really sacrificed everything on the altar of creativity because he just wanted to create. When he died, there were three pictures by his bed: Greta Garbo, Peter Watson and Kinmont Hoitsma. Garbo was a known lesbian, the screen siren of the time and totally unattainable — that’s who he was chasing after. Watson was an unrequited love; Hoitsma, a later lover in the Sixties. Beaton never had a fully fledged love life because even when he was so in love with Hoitsma, he never really let himself go. He eventually said, “This isn’t going to work out,” because Kin was not fitting into his life in London. His priority was creating.

One anecdote that speaks volumes about Beaton…

The time he photographed the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. He was in the church, in the top pews where the organ is, peering down from above and doing these beautiful black ink drawings that are absolutely fantastic, with sandwiches stuck in his hat. This is his maniacal side of creating. Then she leaves, and he leaves and goes back to Buckingham palace to photograph her and the rest of the royal entourage for the rest of the day. Could he not have done one thing? He had to do it all. I think this is what his life was about. But within all that, you have to think of one thing: Who is he probably always sacrificing? Himself. He’s never really leaving room for himself.

You’ll see it in the film. We have Rupert Everett narrating Beaton’s words and when you see it on the screen, it’s much more powerful. You sort of squirm in your chair, going, “Oh, gosh, he really said that?”

His targets…

He had a lot, from Evelyn Waugh to Coco Chanel to Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. There’s an endless list.

On when Beaton was happiest…

We interviewed his butler and he said Beaton was happiest when he was down in the country, just puttering about the garden. That’s what he really loved. He wasn’t being compared, he wasn’t feeling inferior. I think that, although he was the recorder of all these famous people, he still always felt he was an outsider. That sense of outsiderness really stayed with him to the grave.

More to explore in Culture

-

Culture

1.15.26

Cool Girls Who Got Fired

Culture

1.15.26

Cool Girls Who Got Fired

-

Culture

4.21.25

Word of Mouth: ‘Can’t Look Away’

Culture

4.21.25

Word of Mouth: ‘Can’t Look Away’

-

Culture

10.24.24

Word of Mouth: ‘Daughters’ on Netflix

Culture

10.24.24

Word of Mouth: ‘Daughters’ on Netflix

-

Culture

10.24.24

Financial Literacy for Kids? It’s Priceless.

Culture

10.24.24

Financial Literacy for Kids? It’s Priceless.

-

Culture

11.22.23

What’s Your Sign? Sagittarius

Culture

11.22.23

What’s Your Sign? Sagittarius